I can't tell you how good the judges for this weekend's Indiana News Photographers Association contests were. You can find out a lot on the Internet about RJ Sangosti, Barbara Perenic, and Carlos Javier Ortiz, and I encourage you to do so. You'll be inspired, and your faith in the power of photojournalism will be strengthened.

Thanks to their comments, and to the awe-inspiring quality of work submitted by dear friends and other college students, I have here a much better compendium of my year's work than what I had submitted for my College Photographer of the Year (CPOY) entry. I can't enter it, of course, because the contest is over, but I also can't improve if I don't take a critical look at my work and continually edit it. The set of images I should have submitted (whether in a portfolio or sprinkled among the singles categories of feature, sports, and news) is at the bottom of the entry.

Before I get to that, though, I have a few other things to say.

I qualified for the CPOY contest in 2012. I was definitely a student in 2011, when I graduated from IU-Bloomington, and the body of work I could have entered into the contest to be judged in February 2012 included the most in-depth story I've ever worked on: the disappearance of student Lauren Spierer. A month of near-daily work that got me to know volunteer searchers, an anonymous source, and parents Robert and Charlene Spierer was certainly worthy of entry into a contest. I did enter it into the Hearst photojournalism competition, but I never got around to putting together a full entry (including non-Spierer photos) for the CPOY competition that year. As I told a fellow photoj during the weekend of judging for the 2012 competition, I didn't enter because I wasn't in the right place for much of anything, let alone a critical look at my past photo work. I was a mess. A relationship that I had invested too much of myself in had ended horrendously, and I took it too hard to notice that I had a good opportunity to enter my work into the contest. With the notable exception of the Super Bowl (a convenient excuse to do something other than brood about where things had gone horribly wrong), I look back on late 2011 and the first half of 2012 as a time when I let too many good opportunities pass me by, and not entering the CPOY contest that year was certainly one of them.

When I found out about this year's contest and connected the dots to my eligibility, I took it as a second chance, a way to make up for one of the things I had let slip away in those months two years ago. The entry was a hurry-up job, and I focused too much on the portfolio contest and not enough on the singles contests (they provided many more chances to win), but my goal wasn't to win. Even if I hadn't won an honorable mention in features, I would have viewed the entry as an achievement. I rediscovered my love for the craft and why I had loved it in the first place, and I had finally tied together a loose end that had been hopelessly frayed ever since the fall and winter of 2011/2012.

So, that's why I entered CPOY this year. I did it, not to win, but to exorcise. The end of my time at IU felt incomplete, even two and a half years removed, but after this weekend, I finally feel like that chapter of my life has closed. It felt good.

The other thing I want to say concerns my switch, despite my love of photojournalism, to medicine. As I told a few people this weekend, I love journalism, but I've found I'm not the sort of person who can do it every day.

This past year's theme (if there can be a theme) has been rebuilding myself around the thing I loved before journalism: science. I had glow-in-the-dark stars stuck on a wall in a corner of my bedroom, and out of the stars' random arrangement, I found a constellation that wasn't like the 15 or so real ones I had memorized from books and the night sky: the stars simply said, "Hi." (Including the period.) I took quite quickly to math, even completely understanding the non sequitur my first-grade teacher used to explain numbering systems beyond base 10 (I believe her examples were base 8, base 3, and base 12). In the summer after third or fourth grade, my parents took me to Purdue for a dinosaur camp, where I built a cast of a fossil dig, molded a pink apatosaur with blue eyes out of Play-Doh, and made paper money and a board for a game called Dinopoly. In high school AP Biology, learning the transfer of info from DNA to RNA, to amino-acid chains, to the proteins that make our varied lives possible, was the most mind-blowing epiphany I had ever experienced. I also read ahead in the book and discovered the awesome explanatory power of the theory of evolution before everyone else in the class.

I. loved. science.

And I still do, enough that I got a biology minor while getting majors in journalism and Spanish, and enough that I kept up a research-writing job in Mooresville for eight years. My "main squeeze" in college was journalism, but science was always there, prodding me to a fuller and more honest understanding of the world and, oddly enough, improving my relations with other people. I've also come to realize that science, and its applications through medicine, might be the best way for me to make the world a better place. As I keep on truckin' through pre-med classes, the MCAT, and applications & interviews for medical school, I have the desire to improve the world, and the confidence that this is the best way for me to do that, to pull me through.

And that's the gist of why I don't want to dedicate my life to journalism anymore. The thought hit home when Carlos was presenting his work in Guatemala and the South Side of Chicago (to be published later this year), and someone asked him how much of an effect his documentary work has in helping people in those places. Carlos compared his work to that of people who put up mosquito nets in Africa. They can count how many nets they put up; their work saving people from malaria is quite quantifiable. Documentary photography is not like that: you can't count how many conversations you start, or how many eyes you open, or how many minds you change. You have to keep telling yourself, he said, that your work is having a positive impact, because it's much harder to find proof that it is having an impact on the world.

I'm not the type of person that can handle that. I need some consistent feedback (hard data, in science lingo) to inform me about whether I'm doing a good thing for the world. Otherwise, I feel helpless, impotent, that my work is futile. I felt that the most deeply after the Lauren Spierer coverage. The work I and others at the IDS did may have helped to raise the profile of the missing student, and it may have rallied the Bloomington community to help with the volunteer searches, and I may be quite proud of all the work we did. However, after a month, after six weeks, after two and a half years, no progress has been made. She still hasn't been found. How can you feel that you've had a positive impact when the situation is, fundamentally, no different than when you first learned about it?

Maybe this is the starry-eyed idealism of youth, but I feel that my impacts will be more positive, more direct, and more effective in medicine that it would be in journalism. I have a deep desire to change the world for the better, and whether it's through the immediacy of the clinic or through the built-up research that results in a new treatment, I think my desire to make the world better will be more fulfilled in medicine. This isn't to say that it's impossible to improve the world through journalism; indeed, it was people like Carlos, Eddie Adams, Will Counts, Dorothea Lange, Lynsey Addario, Margaret Bourke-White, and others who have showed me it's possible, even a duty, to improve the world. I don't see myself in their company, though. I see myself fitting in better with Jonas Salk, Frederick Sanger, Franz de Waal, Lynn Margulis, Jane Goodall, Mary & Louis Leakey, and others who have used science to expand our sense of self and the world, and to make that world better for other people.

As I told RJ over drinks at the Irish Lion on Friday, I got into journalism because I wanted to force myself to talk to strangers. I liked to keep to myself a lot in high school, not letting others learn much about me besides that I was good at school. I figured the pressures of deadline and getting published would be good incentive to talk to other people. It worked, starting with the high school newspaper and finding fruition in the Indiana Daily Student, and I found ways to positively impact the people I once regarded as strangers. My journey through journalism is something for which I'll always be grateful and never be regretful. I just would rather dedicate myself to, and make the world better through, science and medicine.

...

Wow. All of that introspection was exhausting. I didn't expect myself to write so much.

...

That is all.

Jashawn Hicks, 6, throws a bean bag through a hole in a wooden tooth cutout during the third annual Ivy Tech Dental Assisting Easter Egg Hunt & Sidewalk Carnival on Saturday, March 30, 2013, at Ivy Tech Community College in Lafayette, Ind. The event raised money for the Judy Buckles Scholarship.

Alex Farris

Jashawn Hicks, 6, throws a bean bag through a hole in a wooden tooth cutout during the third annual Ivy Tech Dental Assisting Easter Egg Hunt & Sidewalk Carnival on Saturday, March 30, 2013, at Ivy Tech Community College in Lafayette, Ind. The event raised money for the Judy Buckles Scholarship.

Alex Farris

Indiana University forward Troy Williams falls after making a basket during IU's 89-68 victory against the University of North Florida at Assembly Hall in Bloomington, Saturday, Dec. 7, 2013.

Alex Farris

Indiana University forward Troy Williams falls after making a basket during IU's 89-68 victory against the University of North Florida at Assembly Hall in Bloomington, Saturday, Dec. 7, 2013.

Alex Farris

Lafayette Boxing Club's Tate Sturgeon watches as Kate Mane and Kyle Siple trade light jabs during a workout Tuesday, March 5, 2013, at the club building in Lafayette, Ind. Sturgeon and Mane, along with Luis Pena, Conan Hutchison and other boxers, competed at the Indiana Golden Gloves tournament on March 23 in Indianapolis.

Alex Farris

Lafayette Boxing Club's Tate Sturgeon watches as Kate Mane and Kyle Siple trade light jabs during a workout Tuesday, March 5, 2013, at the club building in Lafayette, Ind. Sturgeon and Mane, along with Luis Pena, Conan Hutchison and other boxers, competed at the Indiana Golden Gloves tournament on March 23 in Indianapolis.

Alex Farris

A member of the Naptown Roller Girls cringes as she wipes feces on a painting during the Art vs. Art competition on Friday, Sept. 27, 2013 at The Vogue theatre in Indianapolis. The competition pitted 16 paintings against each other one-on-one, and the piece with less audience support was destroyed by chainsaw, feces, and other means as determined by a Wheel of Death.

Alex Farris

A member of the Naptown Roller Girls cringes as she wipes feces on a painting during the Art vs. Art competition on Friday, Sept. 27, 2013 at The Vogue theatre in Indianapolis. The competition pitted 16 paintings against each other one-on-one, and the piece with less audience support was destroyed by chainsaw, feces, and other means as determined by a Wheel of Death.

Alex Farris

Joshua Wilson, 3, stands in the way of dancing children marching down a path during a Greenwood Summer Concert Series event on Saturday, July 20, 2013, at the Greenwood Amphitheater in Greenwood, Ind.

Alex Farris

Joshua Wilson, 3, stands in the way of dancing children marching down a path during a Greenwood Summer Concert Series event on Saturday, July 20, 2013, at the Greenwood Amphitheater in Greenwood, Ind.

Alex Farris

Vickie Classen describes a section of her house showing some history of the Morehouse Farm on Wednesday, April 3, 2013, in Lafayette, Ind. Classen and her husband, Dan, bought the property in 2000 and worked successfully to qualify the 1870s house and farm structures for the National Register of Historic Places.

Alex Farris

Vickie Classen describes a section of her house showing some history of the Morehouse Farm on Wednesday, April 3, 2013, in Lafayette, Ind. Classen and her husband, Dan, bought the property in 2000 and worked successfully to qualify the 1870s house and farm structures for the National Register of Historic Places.

Alex Farris

Purdue center A.J. Hammons fights for a loose ball with Minnesota guard Maverick Ahanmisi during an 89-73 victory over the Golden Gophers on Senior Day, Saturday, March 9, 2013, at Mackey Arena in West Lafayette, Ind.

Alex Farris

Purdue center A.J. Hammons fights for a loose ball with Minnesota guard Maverick Ahanmisi during an 89-73 victory over the Golden Gophers on Senior Day, Saturday, March 9, 2013, at Mackey Arena in West Lafayette, Ind.

Alex Farris

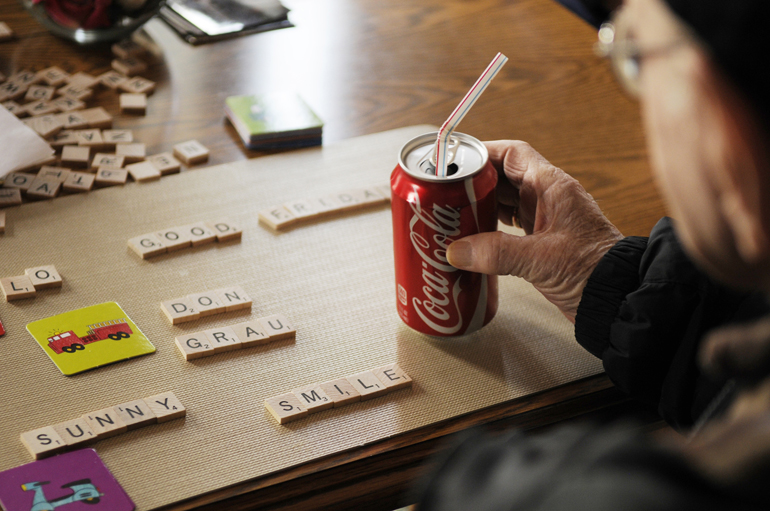

Don Grau, who has Alzheimer's disease, picks up his drink and looks at Scrabble letters arranged on his placemat on Friday, March 29, 2013, at his daughter-in-law's home in West Lafayette, Ind. During visits from IU Health Arnett Hospital nurse Charmin Smith in the Aging Brain Care program, Grau spells words, identifies figures on cards, and talks with Smith and his caregiver, daughter-in-law Peggy Grau.

Alex Farris

Don Grau, who has Alzheimer's disease, picks up his drink and looks at Scrabble letters arranged on his placemat on Friday, March 29, 2013, at his daughter-in-law's home in West Lafayette, Ind. During visits from IU Health Arnett Hospital nurse Charmin Smith in the Aging Brain Care program, Grau spells words, identifies figures on cards, and talks with Smith and his caregiver, daughter-in-law Peggy Grau.

Alex Farris

Jared Barker spits a cricket for distance during the cricket spitting competition at Purdue University's Bug Bowl on Saturday, April 13, 2013, on the Purdue campus in West Lafayette, Ind. The contest, sanctioned by Guinness World Records, debuted in 1997.

Alex Farris

Jared Barker spits a cricket for distance during the cricket spitting competition at Purdue University's Bug Bowl on Saturday, April 13, 2013, on the Purdue campus in West Lafayette, Ind. The contest, sanctioned by Guinness World Records, debuted in 1997.

Alex Farris

Indiana University players watch the pre-game highlight reel as their traditional pinstripes reflect off the hardwood floor before a game against the University of North Florida on Saturday, Dec. 7, 2013, at Assembly Hall in Bloomington, Ind. IU won the game, 89-68.

Alex Farris

Indiana University players watch the pre-game highlight reel as their traditional pinstripes reflect off the hardwood floor before a game against the University of North Florida on Saturday, Dec. 7, 2013, at Assembly Hall in Bloomington, Ind. IU won the game, 89-68.

Alex Farris

Anthony Didion of LaPorte High School celebrates with supporters after running in the 33rd IHSAA Cross Country State Finals on Saturday, Nov. 2, 2013, in Terre Haute, Ind. Didion finished the five-kilometer race in fourth place.

Alex Farris

Anthony Didion of LaPorte High School celebrates with supporters after running in the 33rd IHSAA Cross Country State Finals on Saturday, Nov. 2, 2013, in Terre Haute, Ind. Didion finished the five-kilometer race in fourth place.

Alex Farris

Lorenzo Gutierrez carries a wooden cross as Julio Avila spits water at him during the Living Way of the Cross on Friday, March 29, 2013, outside St. Boniface Catholic Church in Lafayette, Ind. The church's annual Living Way of the Cross portrays the fourteen stations of the story of Jesus' death.

Alex Farris

Lorenzo Gutierrez carries a wooden cross as Julio Avila spits water at him during the Living Way of the Cross on Friday, March 29, 2013, outside St. Boniface Catholic Church in Lafayette, Ind. The church's annual Living Way of the Cross portrays the fourteen stations of the story of Jesus' death.

Alex Farris